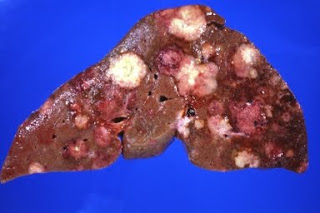

Liver Metastases

Sara Dayton was an attractive 43-year-old high school teacher from Houston. In June 1980, she was diagnosed as having a stage I breast cancer in the lower inner quadrant of her left breast. She was diagnosed, staged, and treated at one of the fine medical centers in Houston. Her cancer was small, nodes were negative, and she elected breast conservation surgery followed by radiation therapy. The malignancy was well differentiated and was both estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive (ER1 and PR1).

On completing radiation therapy, she began tamoxifen and rapidly resumed her normal active life. She was seen by her medical oncologist every 3 4 months. Her chest X-ray, bone scan, and the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 15-3 (CA 15-3) serum tumor biomarkers

were evaluated annually.

Twelve years after Sara had been diagnosed with breast cancer, the tumor markers started to climb. Shortly thereafter, liver metastases were noted on a computerized tomography (CT) scan. Sara’s oncologist advised her that her situation was hopeless and this grim prognosis was seconded by his oncology partner. Neither of these oncologists had observed a meaningful remission with significant extension of life in these circumstances and were attempting to spare Sara the side effects of multiple

courses of chemotherapy. But to what advantage?

When the liver lesion was removed, it measured 1.7 cm, so contained far in excess of the 1 billion cells required for visualization. The likelihood was at least 98% that microscopic metastases existed elsewhere in the liver and possibly the bone. But because they were so small, it was not possible to either remove them or to follow their response to radiation or chemotherapy. So the only way Sara could be followed to determine the success of therapy was to observe an absence of recurrence.

The best estimate of the number of cancer cells that could be eliminated by chemotherapy was 1 million cells. Therefore, if a metastasis of 10 million cells were present in the bone marrow when the liver imaging was done, as many as 9 million cells could remain and the bone site would not be cured even though “good” induction adjunct therapy was given. Furthermore, there was no way even to find tumor metastasis in the range between 1 million and 1 billion cells. This was the reason why Blumenschein routinely prescribed radiation to be given to the whole liver and why he was looking for further benefit to be provided by giving a course of consolidation adjuvant chemotherapy after completing the initial induction adjuvant drug therapy. Hopefully, this program would be adequate to tackle the suspected residual tumor burden.

During the 1980s, patients were becoming increasingly assertive in their search for knowledge about available treatment options for their medical problems. Sara, confronted by a situation which seemed hopeless, with the word “cure” never mentioned, asked for her films and records.

She planned to scour the country for a physician who could offer at least a modicum of hope and was willing to pursue a yet-to-be-widely-accepted course of action, if it seemed reasonable.

Fortunately, the Susan G. Komen Foundation had been started by Nancy Brinker, a dedicated, highly motivated young woman whose sister, Susan Komen, had died as a result of breast cancer. Nancy, herself, was 2 years postmastectomy and chemotherapy. The Foundation was in its start-up phase in Dallas and its primary goal at that time was to raise funds to support clinical research that would provide a cure of this disease which annually was responsible for the death of more than 40,000

US women during their most productive years. Sara had friends in Dallas who knew Nancy Brinker and Nancy was pleased to meet with her and share her insight about the various breast cancer treatment programs operating in the United States and Europe. She, however, was not aware of a program designed to effect cure as an outcome for patients with metastatic breast cancer, other than the many that were conducting adjuvant trials for stage II disease and were fiercely competing for patients.

At that time, only Blumenschein was attempting to find a cure for stage IV breast cancer. In March 1977, he reported on the treatment of patients who had limited sites of metastatic disease with regional therapy prior to chemoimmunotherapy with FAC and BCG (bacille Calmette Guerin), a vaccine against tuberculosis that was used as an immunostimulant. These patients, who were in complete remission because of surgery or radiation therapy when they started chemotherapy, became known as stage IV NED. In the initial reports, there were no patients with limited and resectable liver metastases, but these were soon included and some had positive outcomes. Nancy was aware of these encouraging results and advised Sara to return to Houston to see Dr. Blumenschein or one of his associates as soon as possible.

This was done. Blumenschein recommended that Sara had the liver lesion completely excised and that surgery should be followed by six courses of the current Adriamycin induction chemotherapy combination:

Cytoxan, Adriamycin, and VP-16 (generic name etoposide), abbreviated as CAVe.1 The most difficult task that confronted Blumenschein was to find a surgeon willing to perform what would be considered unconventional surgery. Most physicians would expect to find a showering of very small, almost grossly undetectable metastases throughout the liver when the abdomen was opened and the liver visualized. If this were the situation, the surgery would have been futile and inappropriate. Fortunately,

percutaneous biopsy of an area of the liver that was away from the site of metastases seen on CT scan was normal, and Dr. Robert Steckler in Dallas agreed to do the surgery. He had recently moved to the “Big D” after completing his surgical oncology training at MDA and was well known and highly respected by the MDA staff.

1Etoposide had been substituted for 5-FU at that time because there was a hint that etoposide produced a higher percentage of complete remissions in patients with malignant breast disease than did FAC, but subsequent trials failed to confirm this observation and FAC remained the primary choice for induction adjuvant chemotherapy. This was particularly true for the ACC’91 study of patients with inflammatory breast cancer. Blumenschein regrets that he got locked into CAVe longer than he desired, once he had observed that there was no difference in relapse-free survival and overall survival in FAC-treated patients versus CAVe-treated patients.

The resection was clean and the margins were clear of cancer. CAVe was started 10 days after surgery and Sara completed the six 21-day courses over 18 weeks, receiving a total of 300 mg/m2 of Adriamycin by continuous infusion. Following CAVe, she received three 28-day courses of consolidation adjuvant MCCFUD (methotrexate, cisplatin, 5-FU, and cyclophosphamide with leucovorin rescue). One month following completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, the decision was made to add low-dose late consolidation irradiation to the liver and she received slightly less than 3000 rads. Sara was in complete remission and there was no clinical evidence of cardiac muscle injury. The liver metastases had tested negative for both ER and PR, so tamoxifen was discontinued.

This unexpectedly positive outcome warranted an aggressive followup schedule that consisted of a clinical review, physical exam, chest and liver CT, isotope bone scan, and serum tumor markers every 3 months, as well as routine laboratory tests. To everyone’s surprise, she remained disease-free at her 24-month visit and these extensive reviews were changed to a 6-month interval. At 5 years when everything was normal, someone switched Sara to an annual follow-up visit, convinced that she

was cured.

They were wrong.

In June 2002, 120 months since she began dealing with her first hepatic metastases, her liver CT and her serum CEA level were found to be abnormal. Needle biopsy of the liver lesion again showed metastatic breast cancer. As with many things, however, “time is your friend.”

When dealing with cancer, this is doubly so. In this case, time was very kind to Sara as it allowed her physicians the opportunity to evaluate a host of compounds and protocols active in other cancers, but never given a critical trial against breast cancer.

After Adriamycin was introduced, there began a search for other chemotherapeutic drugs active against breast cancer and, hopefully, noncross resistant to Adriamycin. In an effort to expand the number of effective therapeutic options, some 2 dozen new chemotherapeutic agents were tested for their activity against breast cancer cells. This, as with many other tasks at MDA, was a joint project between Developmental Therapeutics and the Medical Breast Service. Dr. Gerald Bodey from Developmental Therapeutics directed the program. Dr. Hwee-Yong Yap from the Medical Breast Service was prodigiously productive in designing and conducting clinical trials of numerous candidate agents.

This massive effort expanded Sara’s therapeutic options and Blumenschein could now treat Sara’s second liver recurrence with nine courses of a combination of cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, and taxol (CAT), giving her a cumulative Adriamycin dose of 750 mg/m2. When the area of liver recurrence was explored surgically after this regimen, multiple biopsies showed no evidence of cancer. So she received a final course of 5-FU, mitomycin C, etoposide, and cisplatin (FUMEP). As of this writing, Sara is doing well without evidence of disease (NED). Accordingly, Blumenschein counts Sara as cured!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Warning !!!

=> Please leave a comment polite and friendly,

=> We reserve the right to delete comment spam, comments containing links, or comments that are not obscene,

Thanks for your comments courtesy :)